This post is the part I of the video analysis in which I'll elaborate on a few points exposed by Adam Tornhill on a talk presented in the 2019 GOTO Conference that happened in Copenhagen. As he addressed several topics, I've decided to tackle it into different fronts.

In this initial post I'll cover the first half of the video where he approaches technical debts found within a single code base (or repository if you will). There are several points on his presentation that, I believe, are spot on and deserves to be transcribed and better explained. Technical Debts as a concept is something usually underrated by several (if not most of) big companies. The amount of money and man-hour effort spent fixing problems is often pointed as an order of magnitude higher than avoiding it before being released into production.

Lehman Law's

Adam will use Manny Lehman's Laws of Software Evolution as the foundation of his argument during the whole talk. 1:

- Continuing Change: "a system must be continually adapted or it becomes progressively less satisfactory"

- Increasing Complexity: "as a system evolves, its complexity increases unless work is done to maintain or reduce it"

One shall focus on the real issue

As he points out, there's an inherent conflict between these two laws. "On one hand, we have to continuously evolve and adapt our system but as we do, its complexity will increase which makes it harder and harder to respond to change". These are so intertwined that it prevents us to perceive the problems as it is, leading us to tackle "the symptoms more than the root cause".

What he has experienced is somewhat similar to what I've witnessed in the past few years. If we, as technical and business leaders, only monitor the tickets we have in the backlog we might not be able to identify the impact that technical debts impose to our users. Therefore, to actually solve the problem, we need to understand the underlying issue - the root cause of the problem. It might imply on revisiting a software, a component design or even how we approach and process the interaction with the user.

It worth mention that Tornhill is not advocating perfectionism. In general, users don't mind living with one or two glitches in the app as long as it doesn't impact their work routine. But as we neglect the existence of those technical debts, the time to release of new features or fix bugs grows bigger (and faster) than the symptoms experienced by the users.

The clear challenge for product and engineering teams is finding a balance between mitigating technical debt and ensuring the software still delivers valuable experience to its users.

The perils of quantifying technical debt

We really have to consider what kind of behaviour do we reinforce by putting our quantitative goal on technical debt. [...] People like us (developers) will optimise for what we are measured on. That most likely means that we're going to pick not only the simplest task, but we're going to pick tasks that we're comfortable with. [...] That also means that we lack the most important aspect of the technical debt: we lack the business impact.

It's safe to say that, at this point in time, Adam addresses the biggest wound in the current state of the software development industry. We've been putting much more effort on the results (having less tickets in the backlog) than on the outcomes (deliver more value, or provide a better experience, to our users). By simply removing those issues from our sight we are neglecting to solve the root cause of the problem, as it doesn't guarantee our software won't behave poorly in the foreseeable future.

Assessing the technical debt

Cyclomatic complexity2 is probably the most common tool used to identify whether or not a piece of code needs to be revisited due to its complexity. Adam points out, though, that "code complexity is only a problem when we have to deal with it". There's no point in optimizing a complex source that is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

We can combine Cyclomatic Complexity with Code Change Frequency3 analysis. Together they give us a different perspective on how we've been dealing with the software, as we could use it to list which sections of it has been more frequently changed. This metric alone wouldn't be really useful, after all, why should we optimise something that is not complex at all.

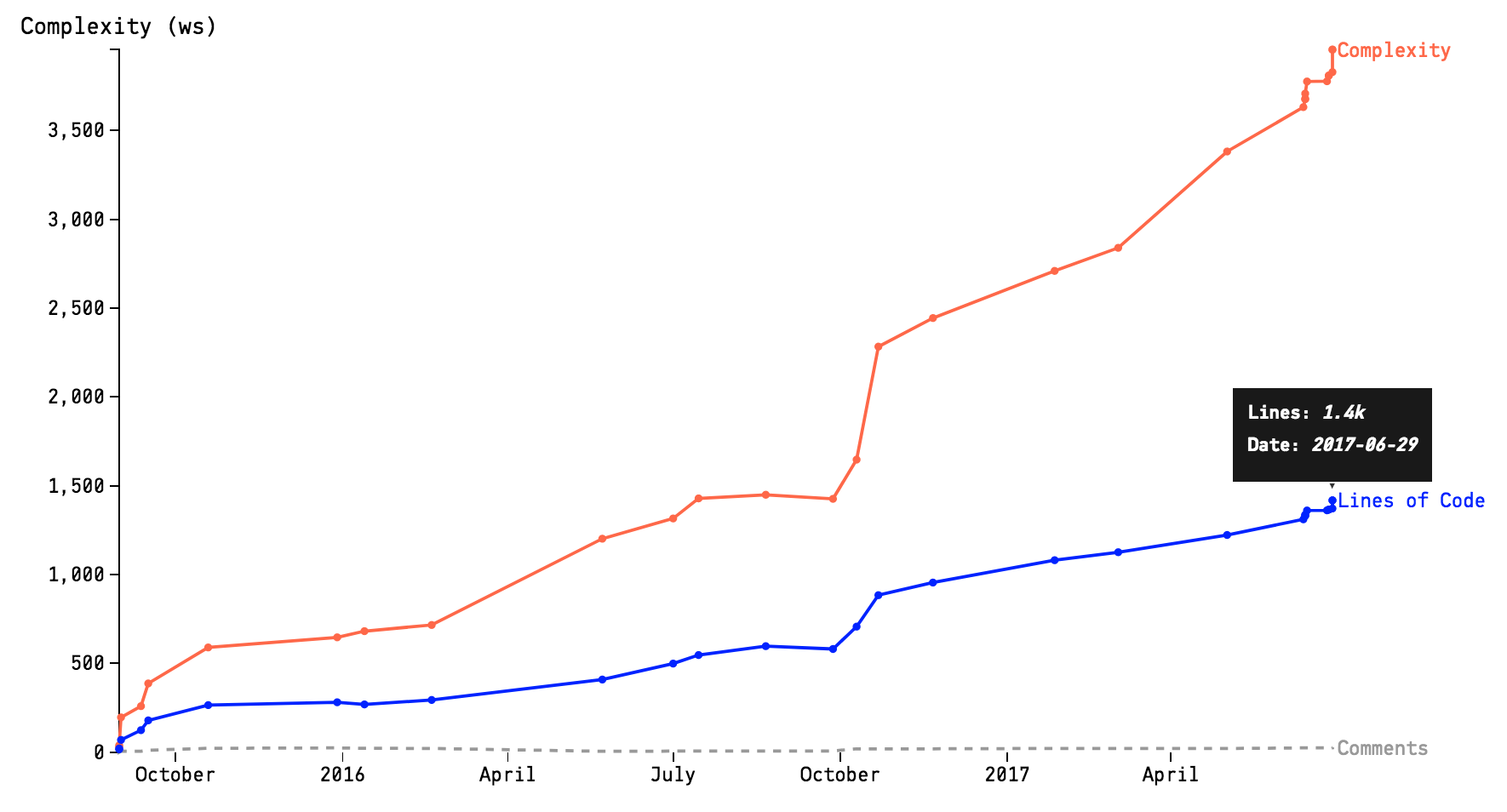

To better understand the process, Adam proposes us to use our VCS tool and to list the most frequently changed files over a given period of time. Once you spotted a file which has been constantly changed, one can be submit each of the changes (as taken from the VSC repository) to a complexity analysis. The result would a timed series of data that we can plot into Complexity Trend chart - as illustrated by the picture below.

Picture taken from codescene.io

Picture taken from codescene.io

Hotspots X-Ray

Refactoring of a given unit of code can be approached in a multitude of ways. Adam emphasised that we should never start a refactor process without taking into account how the team, as a whole, interact with the identified problematic code.

Usually, a big refactor might too impactful to be applied straight into the main branch. It implies that we might need to branch that modifications out. The risk is clear, if the main branch is modified more frequently than the refactor branch, it might never be merged back again.

Reducing the refactor scope is key to succeed here. The speaker then suggests us to narrow down our problematic code base analysis to the function/method level. His ingenious suggestion allow us deliver valuable enhancements into our software within days rather than weeks (in case you're refactoring a humungous class) or even years (if we've decided to completely overhaul the system).

-

Manny Lehman wrote a set of articles between in the 1970s. He would wrap these articles later in 1980 in a book titled "On Understanding Laws, Evolution, and Conservation in the Large-Program Life Cycle". doi:10.1016/0164-1212(79)90022-0

-

Cyclomatic complexity is a software metric used to indicate the complexity of a program. It is a quantitative measure of the number of linearly independent paths through a program's source code. It was developed by Thomas J. McCabe, Sr. in 1976.

-

Code Change Frequency is a measure to identify files that has been more frequently changed. If you are curious to learn how you can address this, you can check out this really interesting repository.